A bird in the hand

The saying “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” resonates with retirees. Many prefer the certainty of high-yielding stocks (the bird in the hand) than finding low-yielding but high growth stocks (the ‘two’ in the bush). Only it isn’t as straightforward as the ancient proverb would have investors believe.

While recent history might have suggested to them that some stocks will indeed pay regular, relatively predictable dividends, they tend to ignore the fluctuating shareprices that accompany these dividends.

The quest for yield means investors favour dividends and, in turn, can be dismissive of a company’s total return - dividends plus capital gain (or loss).

1. Sacrificing growth opportunities

Only looking for companies with a decent dividend yield could lead to being shortsighted and exposing yourself to unnecessary risks.

Collecting six per cent (fully franked, of course) in dividends each year alone is tidy stuff, especially when you can only just get half of that amount in a term deposit. But what if the shareprice is just treading water?

When your total return is your dividend yield, your return after inflation is even lower.

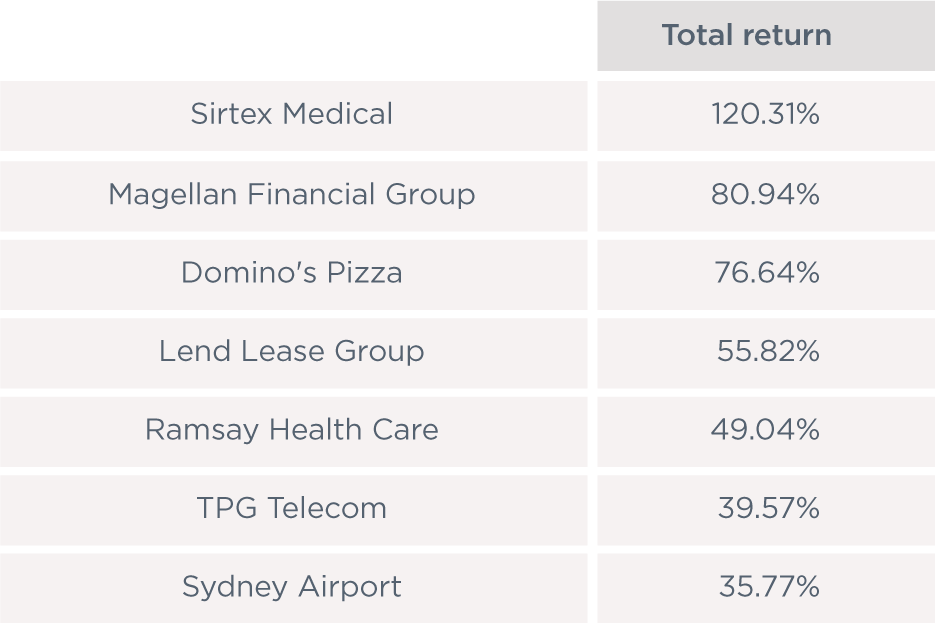

Here are some well known companies that have delivered strong capital growth over the past year.

Source: Bloomberg - data as at 13 February 2015

You don’t need to pick the companies yourself. You can invest with a portfolio manager who specialises in this.

2. Looking offshore

Source: iShares. Data as at 31 January 2015

The numbers of each market are based on the total return - shareprice gains and dividends, speak for themselves. The Australian market has lagged international peers convincingly, with the exception of emerging markets over the past three years and five years.

Just like the point above, it’s clear that getting a decent total return is worth more to you than just a straight up dividend yield of six per cent.

3. Are you looking long-term?

Creating a portfolio that assumes current conditions will last forever is setting yourself up for disaster.

When interest rates eventually rise, shares with a six per cent dividend yield will also need to offer convincing capital growth to make them attractive on a risk-adjusted basis. Will it mean investors dump their equity in favour of bonds and other fixed income investments?

You can’t expect to get a bump in your dividend each year and a shareprice that hangs around a constant price.

Remember, the Australian market is unique in the sense that investors demand dividends and companies deliver. Not surprisingly, this means there is pressure on management to increase dividends as opposed to deploying profits elsewhere to grow revenue streams. The current dollar value of dividends might be sustainable, but increased amounts might be questionable.